Saltsea Chronicles – Translating Ideas to Reality: The Writers' Room

This is a guest post from one of the writers room team – Waterstones award-winning children’s author, artistic director and Deputy Story Lead on Saltsea Chronicles – Sharna Jackson. Read on to find out how the writers room conceived their concepts, and brought them to life.

The writers’ room for Saltsea Chronicles was – from top left to bottom right in the header image –: Char Putney, Sharna Jackson, Harry Josephine Giles, Florence Smith Nicholls, Clara Fernández-Vara, Halima Hassan, Ida Hartmann, Tanuja Amarasuriya, Krishna Istha, with additional work by Leah Muwanga-Magoye.

The second Hannah said ‘...and the crew in this game live on a boat,’ I was sold. I’m obsessed with boats. This one’s mine. Once she described the writers’ room she was creating, consisting of a group of excellent writers working across disciplines, decks were cleared and I jumped feet first aboard the good ship Die Gute Fabrik.

Having never worked on a game like this, or indeed been part of a writers’ room, the impostor syndrome was strong, but I was keen, curious and excited by what we would make, and how we’d do it.

Our colleague, Harry Josephine Giles, has an excellent post about the questions we asked and what we held onto as we developed Saltsea Chronicles. In this post, I’ll talk about a few of our initial processes in the room: the practical side of bringing the world to life.

A fully-remote writers’ room? For a game?

Yep!

As I understand it, writers’ rooms for indie games are rare. I have also heard that many writers – if employed at all – are often brought into the development process (too) late, and have little to no control over narrative. For Saltsea Chronicles, we flipped the script. Hannah and the writers’ room drove the story from the start, and our work led the production pipeline.

The shape of the room changed over the three years of development, with new writers (from first time interns and experienced writers) joining for set periods so as to maximise the voices shaping the world and its writing.

The first iteration of the our room was led by Charlene Putney. In addition to Harry Josephine and me, we were joined by Tanuja Amarasuriya and Clara Fernández-Vara. We were based in the UK, Europe and the US, worked two days a week, with an essential meeting at 14:00 Central European Time on Wednesdays, where we would delve into our ideas and eventually, take ownership of specific tasks.

What tasks? How did you work?

For the first four months, we built our world.

To kick off, we received presentations and workshops from Hannah where we discussed her narrative design, – e.g. the shape of a chapter and how the story and writing would fit into that pattern – direction and aims. We read, played, watched and discussed her references.

We, of course, also brought in our own experiences, influences and must haves. We tested boundaries at this time, too. Working out what we didn’t want the game to be or include was important to our team and ethical pillars Hannah had constructed for us.

We then began to generate ideas across three areas – characters, story and world. To help guide and articulate our thoughts, we worked in tables in Google Docs, pre-populated with questions to help us delve into and interrogate our ideas.

We used character sheets (but also for places and the world) that gave us a framework for quick and easy creation. They posed simple questions which in answering began to construct a character or location. So, for example, when we were coming up with core characters, we would ask ourselves questions like: What would they bring to the crew? Where is their home island – and what impact does that have on their personalities? What do they *really* think caused the Flood? What’s their secret?

For every island we created across the Saltsea archipelago, we would ask ourselves questions about climate and terrain – pre- and post-flood – but also how the communities there deal with conflict and what, for example, justice would look like within.

For non-player characters (NPCs) and shorter story ideas, we created The 100, a Google Sheet where we had healthy competitions to populate it with as many named characters and B and C plot ideas as we could create in short bursts. Sometimes one of the challenges of working on story within a game is context switching between technical demands, structural ones, and creative. By creating a silo of quick-easy to pick up names and fun side stories in one go it made later work much easier.

In addition to constant conversation on Slack, open to the entire company to view and input into, we lived in Google Drive in those early days. Each writer had a specific font colour and left comments, questions and expanded on each other's work. There was incredible ‘Yes! And…’ energy as we walked ideas down unexpected paths.

But we couldn’t (I mean, we could…) generate ideas forever. We had to focus, so …

We swore on the bible(s)

As we honed our ideas, pitched them to Hannah and shared with Nils Deneken and Angus Dick in the visual design team to kick of their thinking, we began to collate our work into three work-in-progress bibles – Character, Story and World – which grew into large, detailed live documents which we edited and updated throughout the duration of the project.

The bibles became invaluable resources, especially when new members of the team were onboarded, and we used them to share our direction and progress with our funders and potential partners.

But, as we began to craft and write each chapter, we quickly found we needed more specific documentation that gave the entire studio more guidance on what should occur, when and how, but wasn’t too prescriptive and constrictive and held space for creativity and happenstance.

This Must Be the Place (and Story documents)

One of my key tasks was then to create the Place and Story documents.

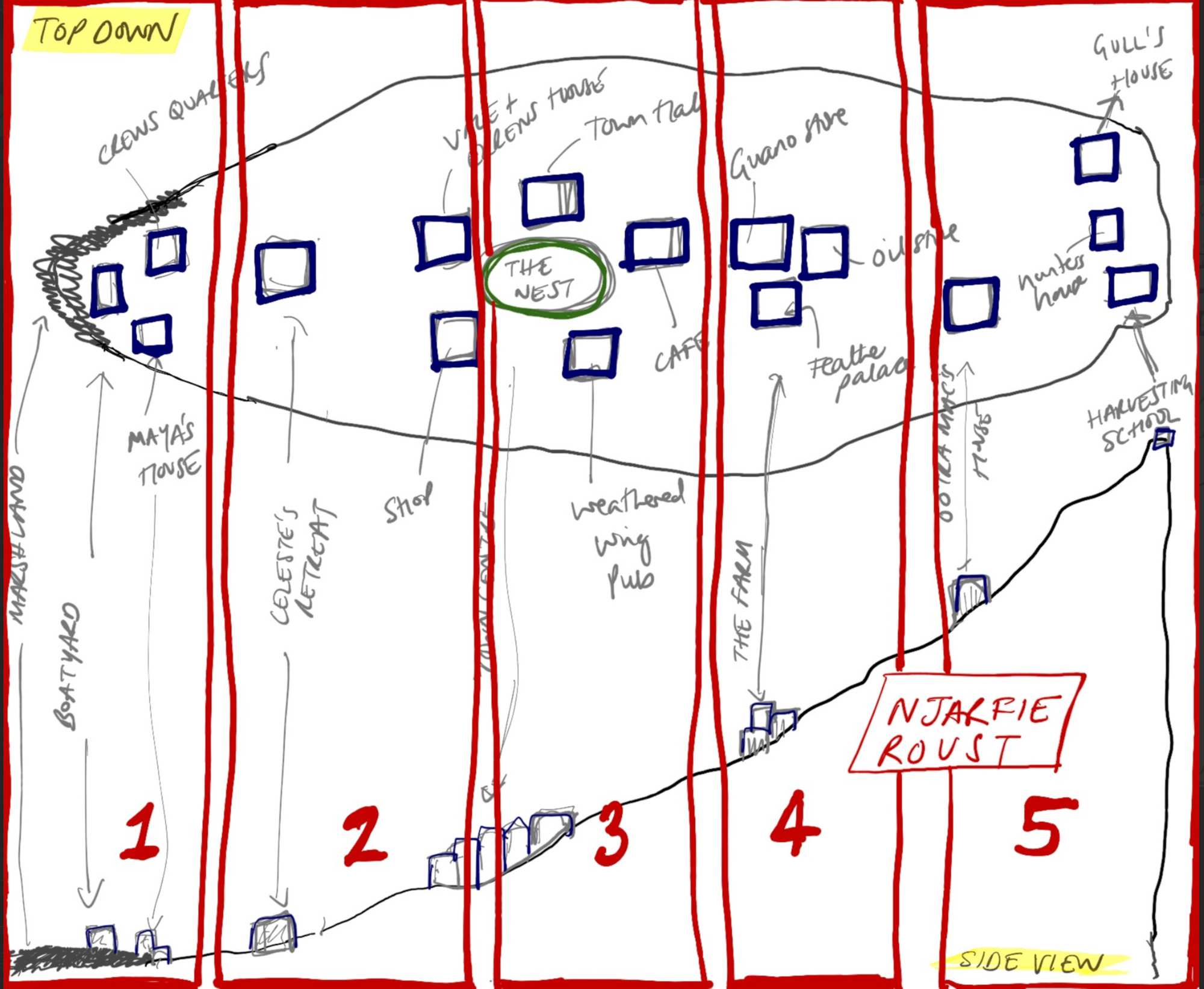

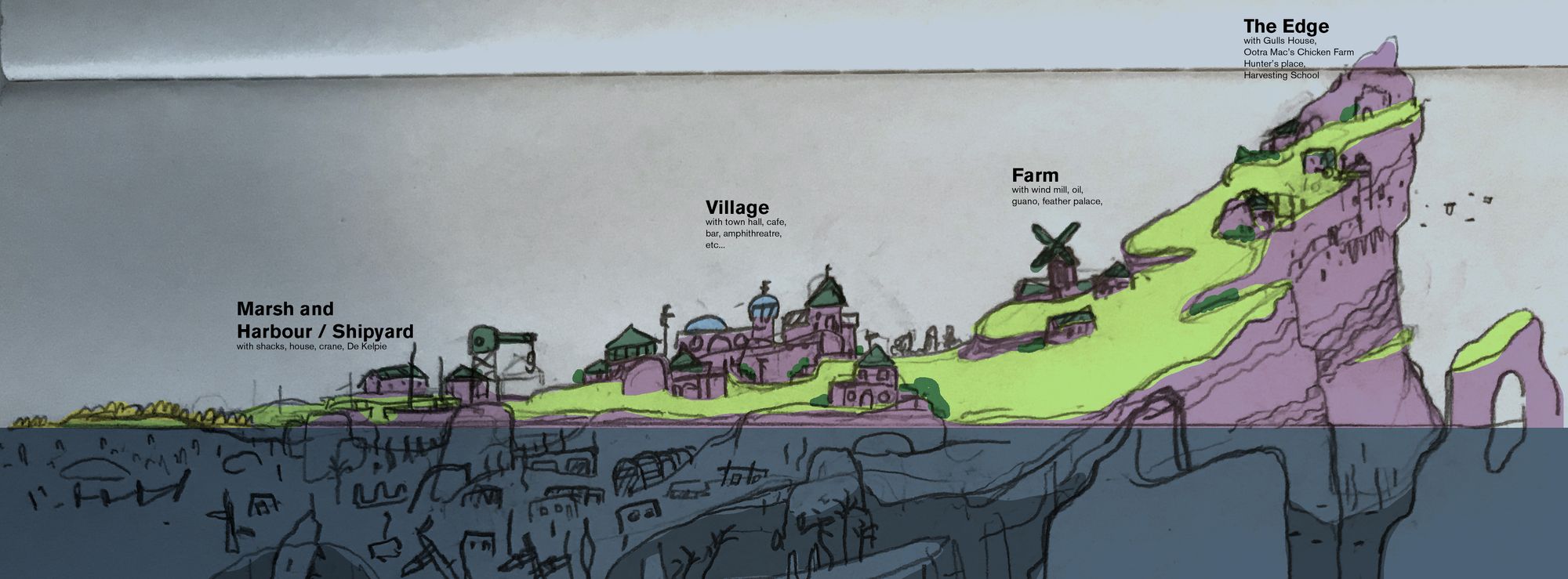

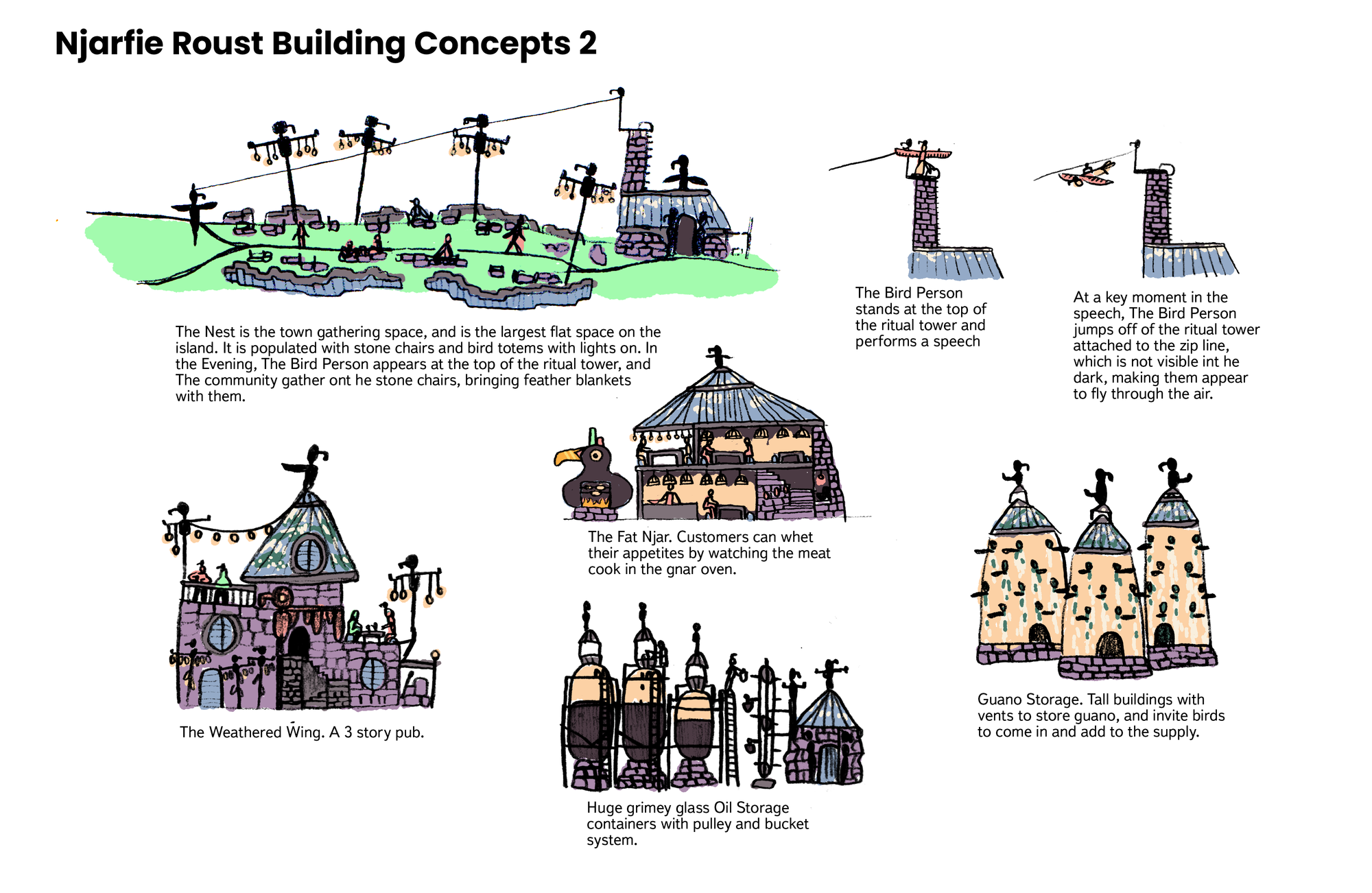

The Place Document was created predominantly for the visual design team. It described the landscape, the flora, fauna and weather for each chapter and the objects our crew would encounter. They included descriptions of the NPCs they would meet – what they might look like and how they behave. The Place Document also included a proposed layout of each island, what buildings (if any) were there, what they were there for and who inhabited them. Instead of using my words here, I would sketch it out.

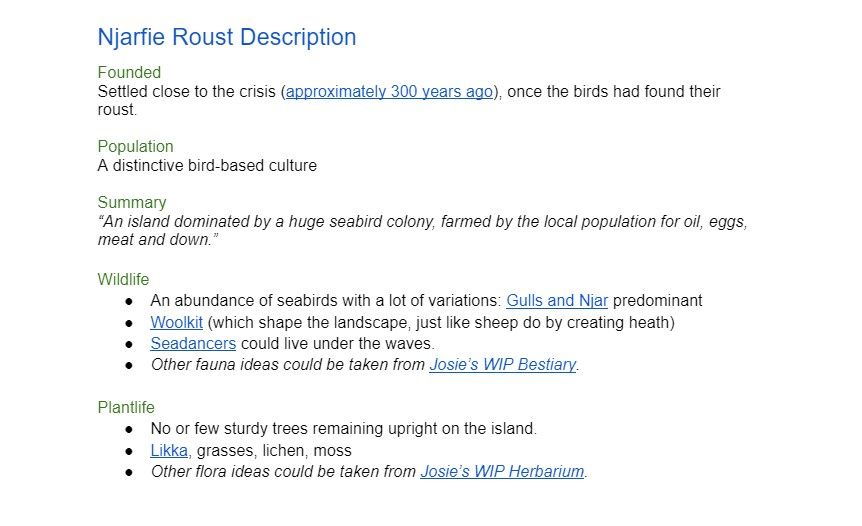

Here's Njarfie Roust, my version, the first sketches from Art, and then the finished article...

My role began to shape up as the person who kicked off each chapter. As others were finishing up writing a previous chapter, I would write a full synopsis for each chapter in the Story Document. Then it would be handed to someone to implement the story tech in Ink (structure, files, titles, variables, and each encounter with a little summary as a note at the top), so that people writing encounters in the game would only focus on dialogue and choices. Again, trying to make it so we weren't split-focussed, everyone was laser focussed on one part of a task at any one time.

The Story Document for each location would describe which members of the crew would be available to disembark and visit the island, and what the main, B and C plots were. These walls of text were then turned into one or two line descriptions for our story actions, the pieces of story you’ll interact with in Saltsea Chronicles.

These were laid out by each location on the island, and on what ‘layer’ they would appear on – most chapters have at least two layers; this is when the time of day changes.

It’s important to know that not all story actions are the same formally. We have a range of interactions in Saltsea Chronicles, with three being key and most common.

- Interjections are one or two lines of text from the POV of narrator describing the scene, or an NPC making a comment.

- Observations are brief conversations between our crew members remarking on their environment or a task ahead.

- Conversations include the crew and island inhabitants and push the story firmly forward.

These don't mean too much to a player, but to us they helped us balance the storytelling, the pacing, characters development, and keep in mind the purpose of our writing.

The Place and Story documents were created in tandem, and mostly in the order a player would progress through the game.

Our team would read and comment, and I would amend, then Hannah would have sight of these documents to sign them off.

After they were signed off, Nils and Angus from the art team would meet Char and me. We’d send the documents around two weeks prior, so we could discuss and refine or raise issues about what we had devised.

Then, once we had cross-departmental consensus and sign-off, it was time to start writing in Inky, while creating documents and technical set up for the forthcoming chapters.

Our documents, and indeed the processes weren’t ‘perfect’, or gospel. They weren’t designed to be, that wasn’t the point. My personal favourite moments were when we heavily edited the story actions if it felt needed by the other writing, requested new variables, spotted missing areas, or cut them completely if they weren't working. Beautiful brutality. But the documents helped us all share an overview in buy in to make that all possible.

We also left room to add things after art had worked their magic – often creating new story actions sparked by seeing their work, or when the technical team developed new features which presented an opportunity to approach a story action or plot point in a completely different way. Our process and documentation were creative constraints; flexible structures used to propel our international, flexible working team through production.

What did you learn from this, then?

Personally, so much – it was an incredible privilege to work on Saltsea Chronicles, so early in the project, with a team of excellent writers in a supportive, forward-thinking studio. Seeing your ideas – your characters, conversations, locales be brought to life so deftly is amazing.

But enough about me. Some takeaways for you, if you’re reading this thinking of running a similar process or learning from it in general.

- Do hire a writer for your game, it’s worth it, I promise

- Do design processes which adhere to your aims, and which are complementary to the needs of your team. So, for example, it was important to us to: 1. be able to recruit widely because of our aims with the writing (we wanted YA, SF and interdisciplinary perspectives); 2. to diversify our pool of potential writers so we had lots of perspectives to inform the world building, and finally; 3. because a very high priority was excellent dialogue skills (meaning that we recruited with that in mind regardless of disciplinary background). In that context we went beyond game writers in our recruitment, but because of that we needed to shape our tools and processes around people with little to no games writing experience. Therefore...

- Do think carefully about how you work with writers from outside of games. While games writing is a very discipline-specific skill, it is something that – with support – writers from other disciplines can learn! Most of all you need to work carefully on the systems of onboarding and training – to not just hope it's picked up, rather to specifically support the development of disciplinary-specific tools, craft etc. Some writing skills can be transferable, but you do need someone taking care of how the writing is integrated into the design of the game (narrative design – in this case we kept that off the plates of the writers and Hannah & Char led as CD & Story Lead), and you do need writers willing to and interested in learning and developing in the context of games (a film writer e.g. can't come in and expect to still write in the same way, they need to be interested in and eager to develop). So – we're not saying a film or theatre or novel writer can instantly become a game writer, but we did design a system of onboarding, documentation and recruitment which skilled our writers up so we had access to that wider pool that met our other aims.

- Do, therefore, train ‘non games writers’ on what it means to write for a game, and make sure, if you have a writers room, there is someone there with experience and time to support them with documentation, tools, and other support.

- Don’t think that forms, format and processes run at odds with the creative process – they most often enable it.

- Do keep track of all your detailed ideas, your characters and your locations. Consistency is not only makes your game stronger, it’s a time saver for your team. Don't spend too much time setting it up though. Worldbuilding could go on forever. Build the parameters, and then if you need more questions answered, discover them in the process.

- Don’t be precious. Ideas and minds change. That’s what makes them great. It's better to have pillars and structure for finding the work than it is a 'finished vision' for a product guiding a process.

I hope you enjoyed this insight into how the story team worked together to produce the story work on Saltsea Chronicles, and hopefully all of this is invisible to you when you play! We can't wait to hear the stories you discover, the people you meet, and the pathways you chart when you play.

Wishlist Saltsea Chronicles on Steam now: