#Redux: The Master of Go

This is the third post in a series called Redux, where Game Designer and Co-Owner Douglas Wilson takes some of his old game design posts from our former 2010's blog, and re-posts them here, sometimes with additional commentary. Some of these posts have been linked from various places, and so this is our attempt to save them from the abyss.

[This post was originally published on February 19, 2012]

Thanks to a recommendation from my friend Mike, I recently finished reading The Master of Go (1951) by Yasunari Kawabata, a famous Japanese author and Nobel laureate. The book, though semi-fictional (some of the names and details have been changed), follows the story of a famous game of Go from 1938, between the Go master Shusai Meijin and his younger challenger, Kitani Minoru.

I only know a little bit about Go, and my grasp of the game’s subtleties is pretty tenuous. Nevertheless, Kawabata’s book was still very enjoyable! A deep understanding of Go might provide some additional color to the story, but it certainly isn’t necessary. The book is primarily a character portrait, as well as a chronicle of a specific subculture and a specific time in history (keep in mind that in 1938, World War 2 was looming close on the horizon). Kawabata's overarching argument seems to be that the Meijin-Minoru game marks a fundamental shift in how Go was played (at least in Japan). The end of an era, so to speak.

The book is an easy read, and I suspect that most game designers will find it rewarding. For the discerning reader, The Master of Go offers some useful lessons about game design and game culture more generally.

Typically, we tend to think about Go as the shining exemplar of “elegant” game design. It features a simple ruleset, yet also boasts infamously complex strategic depth. There’s certainly some truth to that evaluation. But if Kawabata’s tale has anything to teach us, it’s that any competitive game – even Go – is necessarily riddled with awkward ambiguities.

The climax of story, at least as Kawabata tells it, revolves around Minoru’s (Black) controversial move #121. To understand why Black 121 was so controversial – and indeed, even reviled by some – you need to understand three things about the Meijin-Minoru game. First, the game spanned several months. Between each session, the players would break for several days. Second, each player was given a limited amount of total time (40 hours) to contemplate their moves (note that Minoru came close to using up all his time). Third and most importantly, the Meijin-Minoru game was played with a tournament rule that was relatively new at the time (as far as I understand it) – that of the “sealed play.” The sealed play requires that the final move of each session remain unannounced. Instead, it is written down and sealed inside an envelope. The idea behind the sealed play is that neither player should get the break period (several days) to contemplate their counter-move.

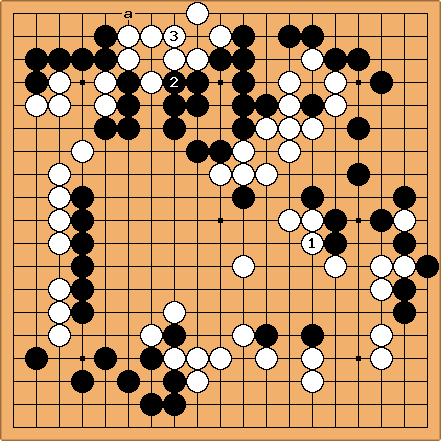

Black 121 was precisely such a sealed play. In fact, the move was so unexpected that the game’s announcer, upon opening the envelope, literally had trouble locating it on the chart. For those of you who actually understand Go, here’s a diagram of the infamous moment:

Instead of playing in the current battle zone in the bottom-right quadrant, Minoru (Black) used his sealed play in the upper-left quadrant. The move was such that it required Meijin (White) to respond in the same quadrant of the board, away from the main action. In essence, Minoru had taken advantage of the sealed play, giving himself several days of extra time (off the clock!) to contemplate what he would do in the region of the board that actually mattered. (Someone correct me if I botched that explanation!)

Meijin (the Master) responded quickly with White 122, without showing much emotion. But during the lunch break, Meijin expressed his true anger, revealing that he had been on the verge of forfeiting (in protest). According to Kawabata, Meijin had exclaimed: “It was like smearing ink over the picture we had painted.” Kawabata, taking Meijin’s side, recounts that he had felt “a wave of revulsion” upon realizing what Minoru had done. Like the Master, Kawabata sees the game of Go as a work of art:

“The Master had put the match together as a work of art. It was as if the work, likened to a painting, were smeared black at the moment of highest tension. That play of black upon white, white upon black, has the intent and takes the forms of creative art. It has in it a flow of the spirit and a harmony as of music. Everything is lost when suddenly a false note is struck, or one party in a duet suddenly launches forth on an eccentric flight of his own. A masterpiece of a game can be ruined by insensitivity to the feelings of an adversary. That Black 121 having been a source of wonder and surprise and doubt and suspicion for us all, its effect in cutting the flow and harmony of the game cannot be denied.”

From there, the story takes another interesting turn. Right before the lunch break, Meijin had played White 130. As it turns out, that move would prove to be the fatal mistake that would eventually lose him the game. Kawabata theorizes that the Master, in his outrage over Black 121, had lost his presence of mind, leading him to make a critical error just nine moves later. We’ll never know the truth of course, but Minoru’s trick certainly casts a certain “shadow” over the game.

Was Minoru “wrong” to play Black 121? Can we indeed call it an “ugly” move?

An Ugly Move?

Perhaps Kawabata’s judgment is not so fair. Interestingly, a number of Meijin’s and Minoru’s contemporaries comment that the time was ripe for precisely such a tactical maneuver. Moreover, some have argued that the Master was notorious for similar such tricks. Arguably, Minoru had simply given Meijin a taste of his own medicine.

Videogame designer David Sirlin, in his book Playing to Win, writes against the notion of the “cheap” move. Sirlin argues that the point of competitive games is to play to win, and that any move is fair as long as it falls within the agreed-upon rules: “The game knows no rules of ‘honor’ or of ‘cheapness.’ The game only knows winning and losing.” As Sirlin sees it, good players respond not by complaining about “cheap” tactics, but by searching for a counter-strategy. He admits that in rare cases, some moves might be so powerful that they do “break the game.” But he claims that these cases are very rare, and that players should, as a rule of thumb, assume that any tactic is fair and continue playing.

Sirlin certainly makes a compelling argument. The problem, however, is that his perspective assumes that the rules are indeed agreed upon and unambiguous. In Meijin’s defence, we might point out that he was playing a different game than he had thought he was playing. Admittedly, using Sirlin’s reasoning one might counter-argue that Meijin can only blame himself for assenting to the sealed play the first place. But whether or not we should “blame” Meijin, Kawabata’s larger point still stands: “New rules bring new tactics.” In adding a new rule to make the game more “fair,” the officials had also changed the very game itself. It wasn’t the same game that Meijin had grown up playing.

The question, therefore, isn’t simply whether Black 121 was “cheap,” but also what changes we should (or shouldn’t) make to existing games. When we add new rules and regulations, how do we change the culture around that game? For Meijin and Kawabata, Go symbolized an entire way of life, both literally and figuratively. We can at least understand why they would feel sad to see that culture transform. Change can be difficult.

Moreover, both Meijin and Kawabata seem to be arguing that winning isn’t actually everything. Romantic or not, their claim seems to be that the “old” culture of Go valued the aesthetics of play, not just the result. Obviously, this argument is somewhat problematic (again, see this contemporary discussion of the controversy). But personally, I can’t help but feel a little sympathetic to that point of view.

The Well-Played Game

If we believe that the beauty of play is indeed located in the back-and-forth between well-matched opponents (see Bernie DeKoven’s work on the Well-Played Game, or Dave Hickey’s famous essay on Julius Erving and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar), then it’s crucial that the games both players think they are playing actually match one another. Possibly, the Master would have insisted on different rules (for example, less total time) if he had known that Minoru would play with such tactics. Arguably, Meijin had already sealed his fate before the first move was even made.

In fact, Black 121 is not the only point of contention during the Meijin-Minoru game. Throughout the story, unexpected issues arise. For instance, when Meijin falls seriously ill, the organizers pressure Minoru into assenting to a modified play schedule. At times, Minoru feels like the Master is failing to live up to the “contract” of how the game is supposed to be played. At one point, he himself comes close to quitting (rage-quitting!) altogether.

Sirlin is therefore a little too idealistic when he writes that “There’s no weaseling out of defeat by redefining what the game is.” Whether we like it or not, there is always a certain degree of gamesmanship in negotiating how, where, and when the game should be played. This applies not only to tabletop games like Go, but also to computer games. Sociologist T.L. Taylor writes about how even a game like StarCraft runs up against rule ambiguities and thorny tournament disputes. As T.L. phrases it, rule negotiation is a “consistent feature” of computer gaming. Total systemization is a myth; it is impossible.

For us game designers, the takeaway lesson is this: new rules and regulations might fix some problems, but inevitably they introduce new ones too. Of course, this isn’t to say that we should necessarily shy away from altering existing games. But Kawabata’s tale does usefully remind us that even a seemingly minor alteration can change the entire culture of a game. Sometimes change is inevitable, but it’s at least worth contemplating carefully.

2022 Afterword

10 years later and I barely remember reading the book itself. But I do remember writing this post! At the time we were working on local multiplayer games via Sportsfriends, so I was thinking a lot about cultures of competitive play, house rules, tournaments, and so on.

Certainly, the focus of Gute Fabrik has shifted since. Still, I think there's a lot to learn here, about how videogame systems are always messily intertwined in larger contexts of social rules and interpersonal relations.

Lead image: Dietmar Rabich / Wikimedia Commons / “Go (13×13) -- 2021 -- 6733” / CC BY-SA 4.0)